Expected Goals Against, Actual Goals Against and a José Sá Wonder Season

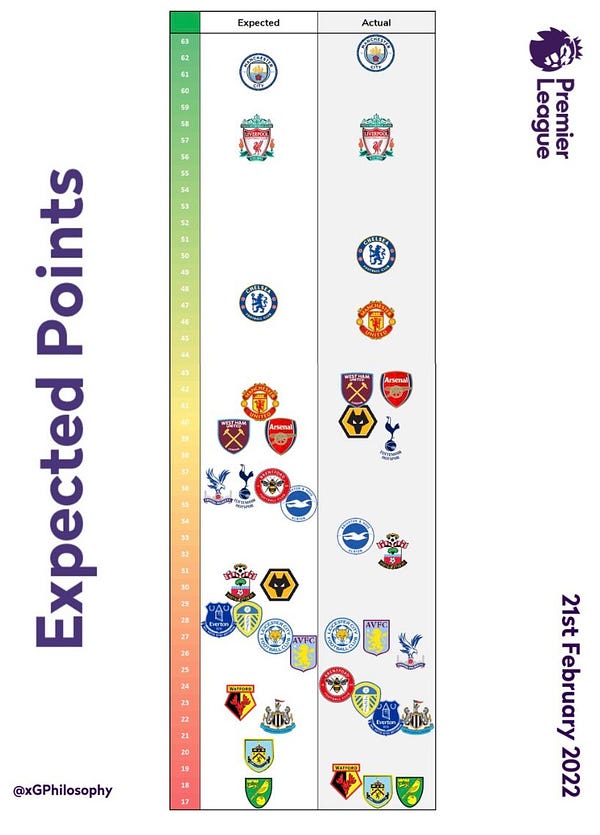

Last week, there was a Twitter post doing the rounds of Wolves fans regarding the difference between our expected points and actual points this season:

This understandably attracted the ire of Wolves fans, but I thought it was worth looking at what Expected Goals are and why there might be a difference between the data and what happens on the pitch.

So first of all, what no earth does ‘Expected Goals’ mean?

I’m not really a big fan of the term Expected Goals, as I don’t think it accurately describes the stat. Think of it more as “Quality of Chances” created or conceded.

Goals are obviously what matters in a game, but there can be a lot of randomness as to when and how they are scored. Let’s look at these two chances in 2022 - one is scored, one isn’t:

So what Expected Goals, or xG, does is try to value the quality of the chance. João Moutinho’s shot on the left is a tough one - he’s 20 yards out, hitting it on the half volley and there are three Manchester United defenders and a goalkeeper who might easily block it. So, FBREF give it an Expected Goals value of around 0.05 - that essentially means that it would be scored once for every 20 shots.

Raúl Jimenez’s opportunity is a lot clearer. The ball has been nicely played into him by Luke Cundle, and although there is a defender making his life difficult, it’s a better chance. It would have an xG value of about 0.4 - if you gave a player 10 chances of this quality, they’d score about five goals.

Expected Points then uses the xG data to calculate how many points you’d typically expect a team to win from the chances created and conceded.

So, let’s first take a look at how our chances created compares to our actual goals scored. FBREF (my data source of choice) estimates that an average team would score about 25 goals from the quality of chances we’ve created. We’ve actually scored 24, so we are pretty much in line with where you’d expect us to be. We don’t create many chances, and as a result, we don’t score that many goals.

It’s at the other end where the big difference is. FBREF estimates that the average team would have conceded 35 goals (the 13th best in the league). Instead, we’ve actually conceded 20, the third-best in the league.

Something that is important to note here. xG measures the quality of the chance when the shot is taken. So, therefore, it doesn’t take into account the quality of the goalkeeper. Something that does take into account the goalkeeper is Post-Shot Expected Goals, PSxG. PSxG looks at the quality of the shot itself. So, if we role that Moutinho shot on a couple of frames, we can see it’s nestled right in the corner. That has a PSxG value of around 0.5; if a goalkeeper faced ten shots of that quality, you’d expect them to save around five.

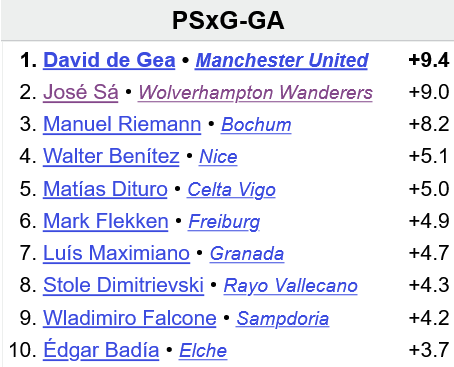

So, this is a valuable tool for measuring how well a goalkeeper is performing, taking into account the quality of the shots faced. This is where there is a large difference between our xG against and our actual goals conceded.

This season, José Sá has saved nine more goals than we would expect the average goalkeeper to, the second best across the big-five leagues in Europe

To give you an idea of how exceptional this is, since StatsBomb started collecting this data in 2017/18, only 14 goalkeepers across the big-five leagues have prevented as many goals.

Now, some of you might be thinking that this is absolutely fine - Sá is a part of the defence and so if his contributions explain the difference between our expected goals conceded and actual goals conceded, then that’s the end of it.

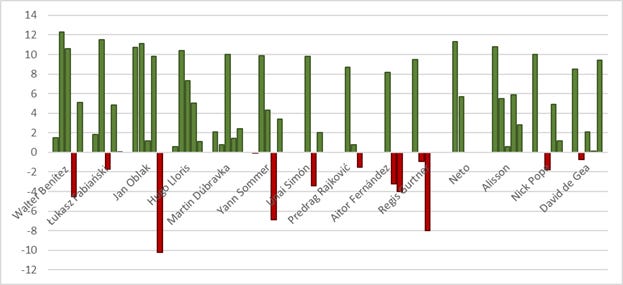

The difficulty is, that this level of performance for a goalkeeper is very difficult to sustain. If we look at the goalkeepers to have prevented nine or more goals in a single season, only Walter Benítez and Jan Oblak have done so again. And Oblak is having a nightmare season, with his PSxG being -10.2 - he has conceded 10 more goals than the average keeper based on the shots he’s faced.

This is not atypical - of the goalkeepers with the 14 best individual seasons since 2017/18, ten have had seasons where they have performanced worse than the average goalkeeper.

This is a very roundabout way of saying that Sá’s form has been exceptional. The problem with performing at an exceptional level, is that it’s very hard to sustain. Unless Sá turns out to be the best goalkeeper Europe has seen for a many year, it would be reasonable to assume that his performances will drop off a little at some point. If that happens, I would absolutely expect us to start conceding goals on a more regular basis.